This post describes the process for setting up a simple blog using Github Pages and Jekyll. It’s super quick and easy, I managed it in just a few hours. All you’ll need is a GitHub account and a basic understanding of how repositories work, specifically how to fork and make changes to files in a repository. If you need help on this front, GitHub has some useful guides you might like to read first.

I’m going to describe how to build a blog from a template, which is the quickest and easiest way to get going. I’ll begin with a quick overview of GitHub Pages and Jekyll, but if you just want the guide, then feel free to skip ahead.

GitHub Pages

GitHub Pages is a service provided by GitHub which allows users to create free, static websites. What do I mean by ‘static’? Static sites avoid a lot of the complexity of modern web design, they don’t need databases, user accounts or scripting. Information is presented ‘as stored’ to the user and is viewed by everyone in exactly the same way.

By using GitHub, I get free (as in beer) hosting, whilst not needing to run a server to host a site and database, to learn any new languages or frameworks, or even having to worry too much about security.

Sure, things like SquareSpace and Medium exist, but this way is properly free, without banners or restrictions on how many articles users can read. I also get a nice GitHub URL as befits a nerd such as myself. I can always change up for my own domain for free if I like (and probably will), and if I decide I want to host it myself at any point, I can.

Jekyll

So GitHub pages does the hosting, Jekyll builds the site. Jekyll is a static-site generator that breathes in Markdown (and HTML and CSS, if you like) and breathes out a site ready to go. There are lots of other static site generators, but Jekyll is well-supported by GitHub pages1, and has been around for ages so it has lots of users, guides and templates.

Building a site

Templates are key here, as we’re not going to worry about Jekyll too much and just use an off-the-shelf layout. The basic process for what we’ll do involves little more than finding a template, forking it to our GitHub repository, making some configuration tweaks, and adding a bit of content.

Step 1: Fork or download a template

The first thing we need to do is find a template for our blog. There are a bunch of different sites offering Jekyll themes, I used jekyllthemes.io, and GitHub has a tonne, but you might also want to check out jamstackthemes.dev, jekyllthemes.org or jekyll-themes.com.

The site I used offers both free and paid templates, but I’m not after anything fancy – quite the opposite – so I browse the free collection till I find something I like the look of.

Clicking through gives us a link to the GitHub page which hosts the template. The README.md gives a bunch of instructions, which we can completely ignore. The beauty of using GitHub Pages is that we can fork the repository, edit our fork and that’s our site!

The next step then, is to fork a template to your own github.

This step assumes you’re working from a GitHub-hosted template. If you were feeling flashy and have paid for something, or used a site which offers files as a download you’ll need to make a new repository and upload the files there.

Step 2: Customize the template

You should now have a GitHub repository containing a template site. Great, now we need to make this our own. Fortunately, this is incredibly easy. First, there are couple things we need to configure on GitHub and in our template’s code, and then we’re already on to writing our first pieces of content.

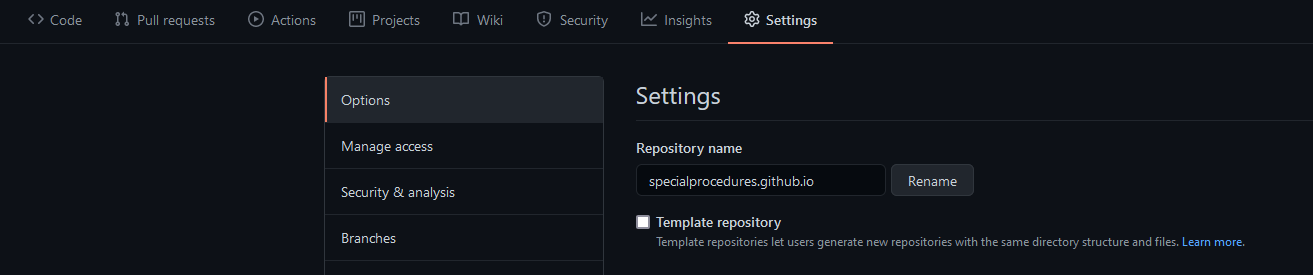

Step 3: Hosting the template on GitHub Pages by changing the repository name

For our site to be available to our discerning readership, we need GitHub to understand we want it hosted on Pages. All we need to do this is to change our repository name using the following syntax:

your_github_username.github.io

So for me, this would be:

specialprocedures.github.io

You can change the name from your repository page by clicking on Settings, and it should be the first setting you see.

GitHub is now aware that you want the repository to be hosted as a page. In theory this means you should be able to navigate to your_github_username.github.io in your browser and see it hosted, but I’ve found that Pages only updates after each commit. So let’s make a few tweaks and come back to it in a moment.

Step 4: Editing the configuration file

In the root directory of your template, you should see a file called _config.yml. The exact fields presented may differ depending on the template you’ve chosen, but I changed the following:

title: Your website title, this will appear in your title bar and landing page

email: Your email

description: A descriptive tag-line for your site

author: Your name

url: This is super-important, it should be "https://your_github_username.github.io"

Don’t forget to update the url field, I missed that first time round and it broke the site’s CSS. There also settings for adding your social media accounts as buttons, to integrate Google Analytics, and to configure markdown options or plugins. Update whatever you want here.

Once you push your changes, this should trigger GitHub into activating your page and you should be able to navigate to your URL to check out your site. Pretty cool!

Step 5: Updating content

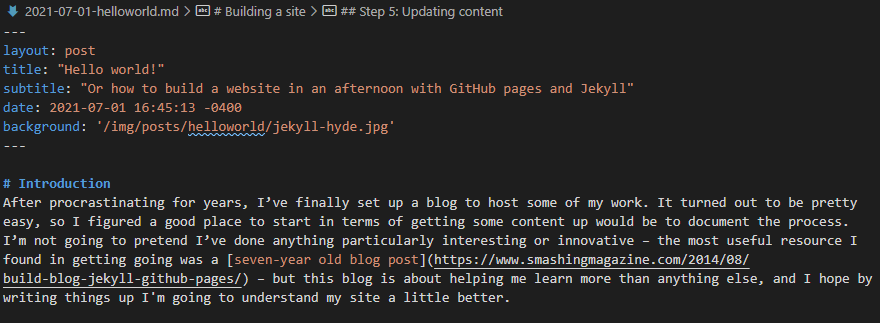

We should now have our site up and running. The next step is to publish some content. Different templates come with different files, but my site has an About and Contact page, and a series of posts. Relevant files may be in different folders within your repository. For me, about.html and contact.html were in the root, with files for posts located in /_posts. All you need to do to update these pages is to find the respective files in your repository, edit them, and push the changes to your repository.

Files can be edited using Markdown, HTML, or even plain text. All of my template files were saved as .html, but if you want to edit in Markdown, you’ll need to change the extension to .md. Each file in your template should come with a header containing a series of fields (e.g., layout, title, date) which will update relevant parts of the page, and then after the header comes your content. Here’s an example from a draft of this very post:

Two important things on content

Creating content for your blog is very straightforward, which to me is one of the the main attractions of this approach. There are however a couple of things that you need to be aware of:

Filename format for posts

If you’re creating a blog-type site, Jekyll expects your files to be named in a particular way. Make sure to name blog posts using the following syntax: YYYY-MM-DD-title.md or YYYY-MM-DD-title.html (depending on whether you’re using Markdown or HTML) for example 2021-07-01-helloworld.md. This way, Jekyll will know it’s looking at a post and will manage the content correctly.

Updates and browser cache

You may find that after pushing a change to your repository, updates may not be visible on your page immediately. If this is the case, try clearing your browser cache waiting a few minutes and trying again.

Step 6: Over to you

This guide intends to get the reader up and running quickly using GitHub Pages and Jekyll, but there may be more you’ll want to do once it’s going. Some of the first things I did at this stage change were working out how to change the fonts and stock images from the template. You may want to do the same, or maybe try and add new functionality, such as categories. It’s also pretty trivial to add your own custom domain name. I spent an afternoon poking around with my code, learning a little CSS, and breaking a few things before I was happy with the final result.

Fortunately, both GitHub pages and Jekyll are very mature products and there are lots of guides and documentation to help. You may want to check out some of the following as you get stuck in:

- Jekyll documentation

- GitHub Pages documentation

- Build a blog with GitHub Pages and Jekyll by Smashing Magazine

Happy hacking!

-

It’s actually built by GitHub founder Tom Preston-Werner. ↩